|

We headed

up last weekend to the Highline Trail locality once again to

collect some microfossil material. Unfortunately, the night before

it snowed up there making finding anything at all very challenging!

I came back with about 35 pounds in limestone, however it was

not chosen based on fossil content so much as being able to find

a clear spot to collect in the snow bound trail. Still, the first

teaspoons of material are coming out of the acid bath, and some

of it was translucent silica. Here are few specimens from that

batch that had some light transmission to try out with the new

microscope.

|

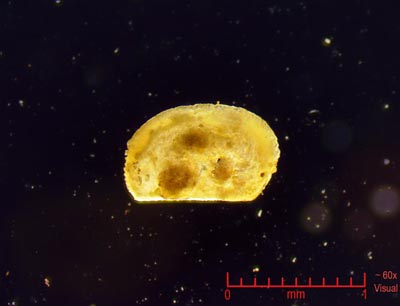

One

type of ostracode is preserved as a half shell, and while less

common than the oval varieties, it has good surface ornamentation.

Back lit shots like this at 60x shows just how much light does

get through. About three were found in the first teapspoon of

acid fines material. |

|

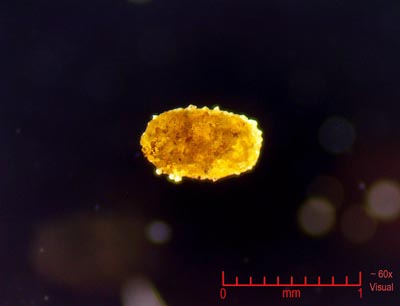

Dark

field illumination, same specimen. Darker areas are where the

ornamentation appears as bumps on the basic shell surface. The

sharp line at the bottom is the hinge. Ostracodes were small

shrimp like arthropods and are still around today. |

|

The

second type of Ostracode we find are the basic ovals. Both shell

halves are still connected here forming a solid ellipse of material.

However dark field illumination shows a stunning straw coloration. |

|

For

some real detail, we go up to 150x. Dark field illumination highlights

the crystals around the edges well. This one is filled solid

internally, I have found in this batch one that is a half shell. |

|

At

150x, bright field illumination (backlit) shows the internal

density of the silica. A flattened lip is seen here at the top,

and the hinge is at the bottom. |

|

For

the internal crystal details, nothing works better than dark

field. Essentially, the more transparent the silica, the brighter

it appears with this illumination. This differs from back lit

which shows the thickness better. |

|

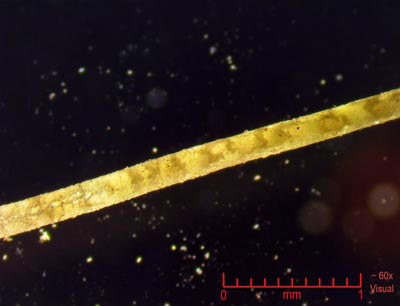

This

is a spine from a productid brachiopod. You can see even dark

field that the repeating dark patterns along the length of the

spine are spurts of growth. |

|

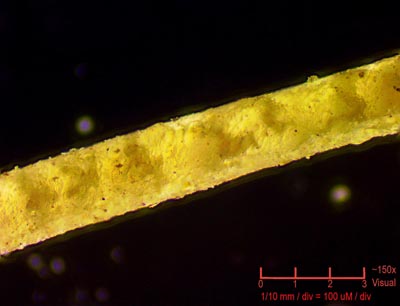

150x

darkfield shows the repeating paterns better. Darker means slower

growth with higher density and lighter is fast. This correlates

most likely with either tides, or perhaps daily cycles. |

|

For

the best view of the growth lines, back lit (Brightfield illumination)

shows it best. While not as asthetically appealing as dark field,

the growth patterns are much better highlighted. |

|

Found

in the first batch were dozens of red sand grains. But was the

quartz actually red, or something else? We can see from this

dark field close up that the red coloration is caused by red

translucent iron or manganese stains on the clear quartz crystal.

60x. |

|

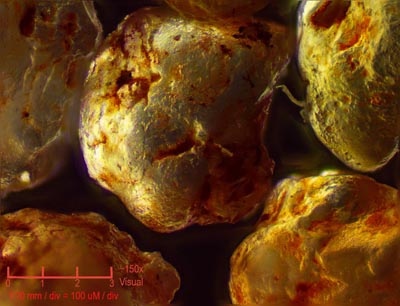

Close

up at 150x, dark field. The red stain can be seen to not only

coat the grains, but fill in any recesses. The grains are well

rounded and certainly have traveled far from thier source on

the coast. Wind borne sand storms would be common during the

Permian times, with the nearby Sahara type deserts lining the

shore. The red Schnebly Hill Sandstone is the main terrestrial

bed for the sand deposits. |

|